ICO is a video game that makes me feel things. Things that I can’t quite describe.

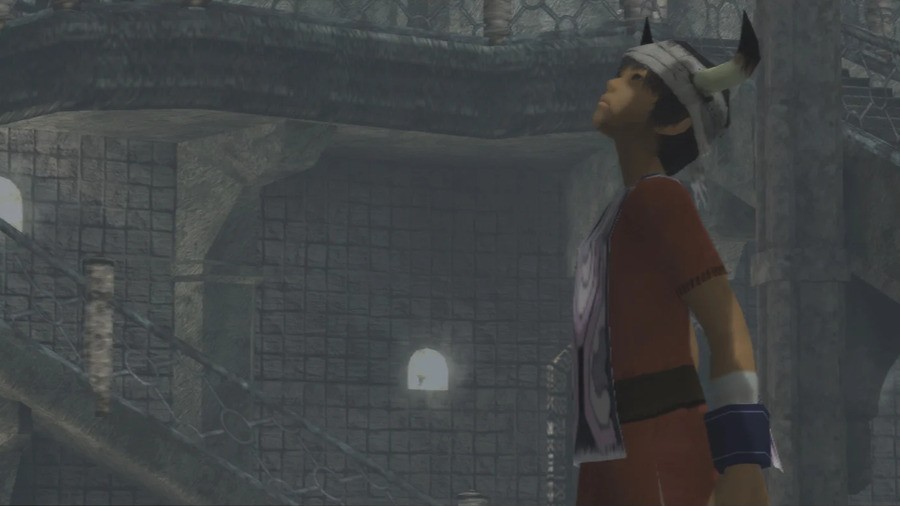

Ever since I first stepped foot in the castle’s plundered hallways, heard Ico’s footsteps echo through the abandoned corridors, and practically felt the gentle breeze roll through its silent, long-forgotten courtyards, it’s a feeling I just haven’t been able to shake.

Its ethereal, dreamlike world – Ghibli-esque in its feel – is so steeped in mystery, drowning in atmosphere, and downright well crafted, that, in the years that have passed, I’ve almost convinced myself it’s a real place.

It’s one of only two games that have ever made me cry actual tears (well played, The Last of Us) and it’s been perched at the tippity-top of my all-timers list for a long while now, despite the best efforts of INSIDE, Celeste, and The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

But we have a strange relationship, ICO and I – in more ways than one.

A Changing Landscape

Despite releasing in Europe 21 years ago, it wasn’t until much later – in 2013 – that I first got my mitts on ICO in the form of the ICO & Shadow of the Colossus Collection for PS3. To my surprise, I found it had aged like a fine wine.

In hindsight, the shock was unwarranted; there isn’t really all that much in ICO to age. In some ways, it barely even resembles a video game – at least, not one of its time.

In 1997, just as the industry was fawning over full FMV, multi-CD-ROM epics like Final Fantasy VII, Fumito Ueda – who would famously go on to create Shadow of the Colossus and The Last Guardian – was envisioning a different kind of experience.

“I don’t personally like very complicated games,” he told CONTINUE magazine in 2005. “If there are too many stats and numbers, I lose interest right away”

And so, while the bulk of consumers were coveting increasingly complex and sophisticated experiences, Ueda kickstarted development on ICO, a game he would later come to describe as “defined by what is not there”.

It was this minimalistic, design-by-subtraction philosophy that acted as the guiding principle for development, and what would ultimately make ICO so very unique.

Less Is More

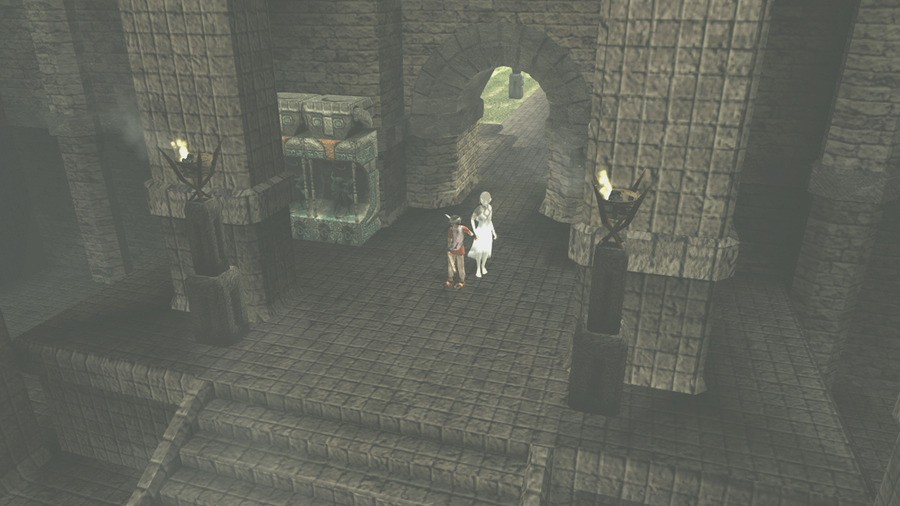

At its core, ICO is a very simple story of boy meets girl, and in order to thrust that emotional bond into the spotlight, any elements that were considered too gamey or distracting to the central mechanic were stripped away entirely.

There’s no quest log, no navigation system, no mini map, or convoluted combat mechanics. No health bars, skill trees. or weapon upgrades. No character customisation, side quests. or dialog options. There’s barely even any music – although what is there is absolutely sublime.

What remained was beautiful simplicity – a boy and a girl, holding hands.

“I wanted to create something no one had ever created. Whatever genre or type of game I made, I knew I wanted to do something unique. I also had this feeling […] that the gameplay needed to be simple.”

In that sense, Ueda and his team succeeded; there was truly nothing like ICO on the market at the time. Regrettably, though, that originality turned out to be to its detriment; simply put, ICO lacked the blockbuster appeal of 2001’s heavy hitters.

Games like Metal Gear Solid 2, Grand Theft Auto III, and Devil May Cry were incredible showcases of the recently-released PS2’s power. They were bigger, flashier, more cinematic, and far more ambitious than anything that had been attempted during the previous generation.

ICO, for all of its incredible qualities, was none of those things. Its use of keyframe animation and bloom lighting was certainly impressive for the time, but its development roots were firmly planted in the PS1 era. It was pretty, it was unique, but it wasn’t – mechanically speaking – anything that couldn’t have been done before.

Thankfully, history has looked kindly upon its more subtle sensibilities, and it’s since gone on to become a cult classic, a defining game of its era, and one of the most influential games of all-time.

Dark Souls creator Hidetaka Miyazaki said it awakened him to “the possibilities of the medium”, acting as the catalyst for him to pursue a career in game development, while Guillermo del Toro heralded it as a “masterpiece”. Quite rightly, too.

The Castle in the Mist

ICO’s castle is enchanting. It’s simply the most believable video game world I’ve ever inhabited.

You aren’t told of its existence through hushed legend or passed-down tales. There’s no 20-hour pre-amble leading up to a dramatic siege. You simply wake up within its dungeons, and are left to your own devices to uncover its mysteries. For a game that’s literally about holding hands, ICO couldn’t be much less of a handhold-y experience.

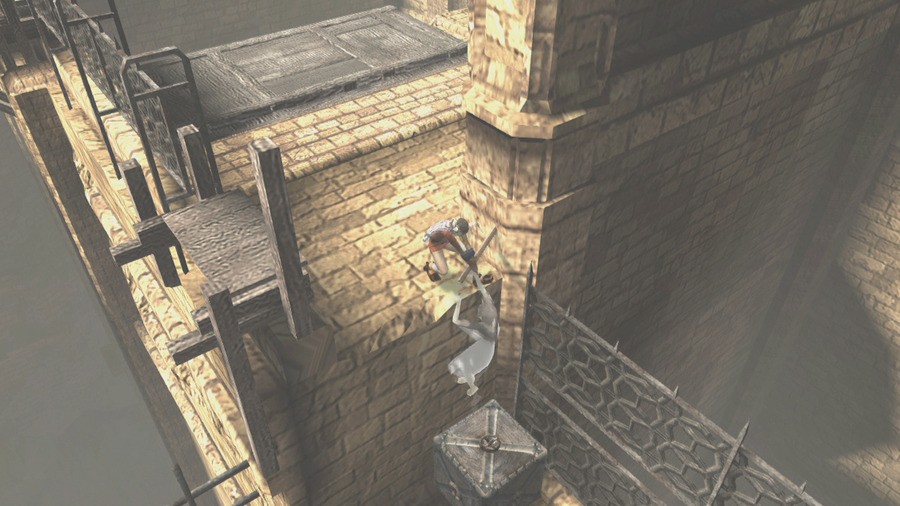

Exploring the castle is instantly captivating. Everything about its design, construction, and implementation is so staggeringly perfect that it genuinely feels like a place that exists in the real world. It doesn’t hide behind smoke and mirrors. It’s not simply a hodgepodge of fragmented, claustrophobic rooms, or a linear series of closed-off, one-and-done areas with invisible walls, hastily pieced together.

Its purposeful arrangement of interconnected rooms, chambers, courtyards, and bridges all make for an unparalleled sense of place, and as you delve deeper into its heart, you’ll climb high atop its battlements, see its walls sprawling off into the distance, and look back on towers that you’ve already scaled.

You’ll gaze out across the impossible bridge that leads to the distant mainland and feel hopelessly trapped, lost, and alone. You’ll see the sun bouncing off the distant cliffs as the birds soar across the sky, listen to the piercing breeze, and for a moment, you’ll swear you can almost feel it. You’ll sit and wonder, “Where the hell even is this place? Who built it? And where did they all go?”

It oozes atmosphere through its visuals and soundscapes, but also via a number of clever design choices, such as the camera system. Rather than a more traditional, over-the-shoulder affair that closely follows the protagonists, we watch Ico and Yorda struggle through the castle from afar.

It seems a fairly inconsequential detail on the surface, but the effect it has on the overall feel of the game cannot be overstated. Through it, the castle becomes not just another video game environment to run around in, but a character unto itself – it’s living, it’s breathing, and it’s watching Ico with us.

It also reduces Ico from a powerful, combo-unleashing video game hero that the camera swings, pans, and struggles to keep up with, to merely another lost little boy, with a wooden stick, trapped within the labyrinthine sprawl of this ancient castle. He’s just passing through this timeless fortress, like countless forsaken souls before him.

You Never Forget Your First Time

In March of last year, I drove the NC500 – a 500-mile road trip around the north coast of Scotland – with my brother. We absolutely nailed it. There wasn’t a single flippin’ caravan on the road, nor a cloud in the sky – a fact which, if you’re familiar with Scotland’s climate, is nothing short of a miracle.

If we drove it another 50 times, we’d never experience it that perfectly again. So we’ll never try.

The same is true with my experience of ICO. That first playthrough back in March 2013 was so completely and utterly perfect that I boxed the memory of it up and sealed it away in the loft of my mind forever. And while the temptation to revisit my old friends admittedly crops up from time to time, truth be told, I’m a little bit scared to.

I’ve read plenty of LTTP threads about ICO since completing it 10 years ago, and I’m weirdly petrified that maybe it’s not the flawless game that lives on in my mind. Maybe this time, the enemy encounters will be repetitive and dull. Maybe the platforming will be clunky and imprecise. Maybe Yorda will try to unalive herself at every given moment.

But when I played it, they weren’t, it wasn’t, and she didn’t. And that’s the way I’ll remember it, thank you very much.

Perfect Moments

In his review for The New York Times, Charles Herold summed up his thoughts by concluding: "ICO is not a perfect game, but it is a game of perfect moments."

If I had to guess, Mr. Herold probably had the legendary windmill scene fresh in his mind when he wrote that summation, but my perfect ICO moment was something altogether less scripted.

I remember drifting in and out of that hazy, peaceful state between sleep and the waking world. It was March, longer spring days were on the way, and the birds were chirping away outside – but another beautiful noise was filling the room. Heal – the game’s heavenly save screen music – was spilling out from the TV. It had rocked me to sleep.

I perched on my sofa – already completely besotted with the game at this point – looked at Ico and Yorda on the screen, and couldn’t help but form a wry smile; they were perched on a sofa, too. Just like them, I’d fallen asleep on the couch, to that ethereal save music.

It was at that point that I honestly felt like some sort of symbiosis had occurred, and the screen was in fact a mirror. Me and this game were one now. I cosied up in pure, dream-like ecstasy, and let ICO’s lullaby softly carry me away to the land of nod once more.

I genuinely couldn’t recall feeling that blissfully at peace before, and ten years on, that music still makes me feel things.

Sincerity Isn’t So Scary

I turned 30 last Saturday – roughly the same age Fumito Ueda was when ICO released. And, like him, I find myself craving simplicity as the years roll on.

To change tack slightly, the same is true of Matty Healy – front man of Brit pop-rock band The 1975, and another 30-something whose world I find myself caught up in recently. He built his career on the sort of wildly pretentious and trite lyricism that only an A-Level Philosophy student would be impressed by.

But with his latest album, the words have taken on a much more earnest flavour. When asked by Amelia Dimoldenberg on one of her famous Chicken Shop Dates to name his favourite lyric off the band’s latest album, he somewhat surprisingly chooses the relatively unseasoned “I’m in love with you”.

“Out of all the lyrics to pick, you’ve chosen 'I’m in love with you,' which anyone could say?” she questions.

“Exactly,” says Matty.

The angst and tryhardiness of teenage years, the uncertainty of early-20s life, and the existential crises that your mid-to-late 20s can bring about – they all seem to be melting away as I get older, leaving behind a newfound calm, clarity, and contentedness with the person I am.

It’s a fairly laboured point I’m hamfistedly attempting here, but what I’m trying to say is: simplicity is underrated. And ICO is a reminder that, no matter what life throws at us, all we ever really need is someone to hold our hand. And what could be more simple than that?

Comments 29

Shadow of the Colossus got a remake, why not this game?

ICO is a favorite of mine from the PS2 era. Sadly, Sony left it to rot on the previous ecosystem. I'd love a remake. Just updated graphics needed. Everything else can remain the same.

An absolutely legendary game for sure. I think its minimalist approach is even more noteworthy in this era of bloated, overly long games.

Ico is in my top 5 all time. SotC I hated as it seemed empty and much more gamey. TLG seems to me a blend of the two.

And I was devastated when Ico wasn't and still isnt available in any form on PS4.

On release it mave have been a defining game. It may now be a cult classic, but will soon be nothing more than a memory if Sony doesn't allow people to experience it. Great article BTW!! Cheers!

An utterly beautiful piece of writing for an utterly beautiful game - fantastic memories of Ico, and like you, I'm not really in a rush to go back. The wonderment still lives on in my mind over 20 years later...

One of the few games that are really masterpieces. It was the inspiration to a number of games, and is one of my favorites since PS2. I never have played nothing like that and still not. Every time I see a main character protecting and sharing the screen with another, more fragile one I remember this game. The last of Us, God of war, Resident Evil 4 are just a few examples. It also inspired my favorite developer (From Software) so much. Ico is a must play for any person who likes videogames.

I enjoyed my time with ICO back on PS2, but I had no idea it existed until after I played Shadow of the Colossus. I was bummed out when I found out the North American version cut out some extra content and has the vastly inferior box art. Thank goodness for the HD PS3 port!

Ico was such a strange game the first time I played it. It was so quiet and tranquil and honestly unlike anything else I knew at the time and, unlike many of its flashier contemporaries, it’s aged very well, arguably better than any other PS2 title. What a lovely reminder to reconsider this classic title.

I loved Ico. Would love a Bluepoint-style remake.

Just hurts reading through this, loved the hell out of Shadow of the Colossus and the Last Guardian, they're probably my favorite two ps exclusives.

But that ico+sotc bundle is way overpriced (30~ sth) here so I could never play it 😭

Very timely, as I just played through Ico for the first time earlier this month. Twenty years later, it didn't blow me away anymore and the combat's definitely a little so-so, but it was still a refreshing experience to play among other massive games of today, as mentioned, and I wish Sony (or any big studio, really) would put out games like this still.

That save screen music though. Hearing that was actually what prompted me to finally play the game and it's a real stellar piece of music.

In my eyes it's the best game ever made. I've not played a game since that invoked such emotion.

Big fan of Fumito Ueda! (Japan Studio) Very emotional, awesome music, special design, ...

I've not long completed this brilliant game on the excellent PS2 AetherSX2 app on Android.

Lovely article and retrospective and you can no doubt see from my profile pic that I’m a fan of the horned one. Easily one of my favourite games of all time and indeed a masterpiece. The Last Guardian came close to repeating its awe and excellence and SotC wasn’t too shabby either (but the weakest of the three in my view but it’s still a bloody amazing game). Happy Birthday to one of the greatest games ever made and kudos to Ueda. Here’s hoping he gets another wonderful creation out before I’m 50. I tweeted him after completing TLG and he liked my tweet (or one of his admin bods did). One of my proudest Twitter moments.

One of the best PS2 titles hands down.

Can y’all do more of these please ? maybe midnight club ?

Ico was an absolutely sublime experience back on PS2. I loved every minute playing it and yes, it also moved me to tears in the end. It was also one of those games of that era that went off-grid to offer players something different than the mainstream, as was the case with games like Rez, Shadow of Memories, Okami, Metroid Prime, Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time to name but a few. I would be ecstatic to see a modern remake (I’d really love to play Ico at 60fps), but I am content with the original and the PS3 remaster.

i need a remake of this one so bad, its sad that you cant play it if your country dont have ps now

Great article. I played it on the HD collection less than 10 years ago and really enjoyed it. Would be hesitant about going again especially on streaming through PS+ (if it's even on there) but a re-remaster would be welcome I reckon.

It's such a unique game, it has this amazing feel to it. I can't wait for whatever is next from Fumito Ueda.

Have the original and SoTC on PS2 and the combo HD pack on PS3. Think the PS2 version is the ideal ones, as the HD just seems to be much too sharp and lost its dream like foggy graphics.

@CasuallyDressed Wonderful article. Beautifully written and very touching. I can really relate. I have a similar relationship with Shadow of the Colossus, which I often cite as my favorite game of all-time. Ico was also a seminal experience.

Just had to come back and comment that I literally had the same experience, and it's why I always list my top 3 games of all time as Ico, MGS, FF7.

I remember feeling such a spiritual connection to saving the game on the couch, that I didn't move for hours. I took a nap, right along with my characters, and for a moment just relished in the peaceful scenery and animations of the characters. Yorda's feet swinging and Ico (or boy) getting a much needed rest from swinging at baddies and solving the intricate castle.

I can see how folks like Neil and Souls game were inspired by it, AI companions and intricate level design are very popular today, the roots began with Ico.

I really hope Bluepoint does a remaster. It being only on PS2/PS3 is criminal.

Really well written and lovely piece of journalism, thank you!

Ico is and was a work of genius. Its stunnig aeshetic was beautifully framed and directed to make the best from its vision and the gameplay ably demonstrated that less can be more.

When this game was first released I was working in Bullfrog on Dungeon Keeper 2, and I remember as we got thre first copy in, the whole team trying to gather round and see a first play through..There were collective intakes of breath and mutters of 'wow' as we opened each new vista.

Later , as I got to finish the game myself, I was moved to tears by its ending, which I remember as it was only the second time a game had made me 'tear up' ( FF7 and ariel had been the first).

A beautiful and timeless game that will forever be in my memory.

My first memory of this game was watching a local drug dealer play it when I was buying some weed.

So I was stoned outta my mind, sitting on his worn couch, looking at this strange game through a dense fog of marihuana smoke... surreal experience.

Must have been 2001 or 2002. Been one of favorite games ever since.

Thank you for the article. I really enjoyed reading it. Brings back a lot of memories. I also never went back after finishing it.

I remember seeing ICO on sale, I think in HMV on Oxford street, I didn't have a PS2 at the time, but I almost bought it just for the great cover art. I finally played it on PS3 in the HD collection with Shadow of the Colossus and it did really impress me, though equally I've not played it since, it is a very memorable game.

“There’s no quest log, no navigation system, no mini map, or convoluted combat mechanics. No health bars, skill trees. or weapon upgrades. No character customisation, side quests. or dialog options.”

A lot of that is stuff I hate from modern games. Probably explains why I like this game so much. And that’s not nostalgia speaking. I first played this at the start of 2020. How did I go so long without experiencing this amazing game?

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...