With the welcome announcement that MediEvil is getting a 4K remaster on PlayStation 4, we dig deep into the archives to unearth a piece on the making of the PSone original, penned by Editorial Director Damien McFerran many moons ago.

Video games are fundamentally about escapism. It’s unsurprising then that the vast majority of video game heroes fall into archetypal stereotypes; muscle-bound and handsome for male leads or ample-breasted and stunningly gorgeous for female characters (Lara Croft, step forward). Bearing this in mind, the choice of lead for the hugely enjoyable MediEvil series is an odd one to say the least; the undead Sir Daniel Fortesque is neither muscle-bound nor suitably heroic. In fact, he’s a complete failure as a hero.

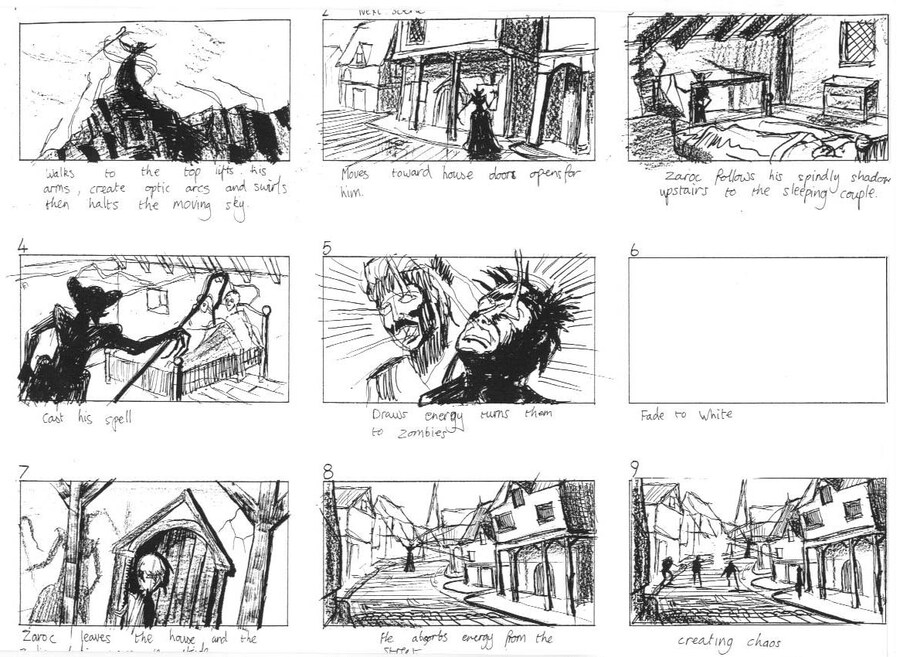

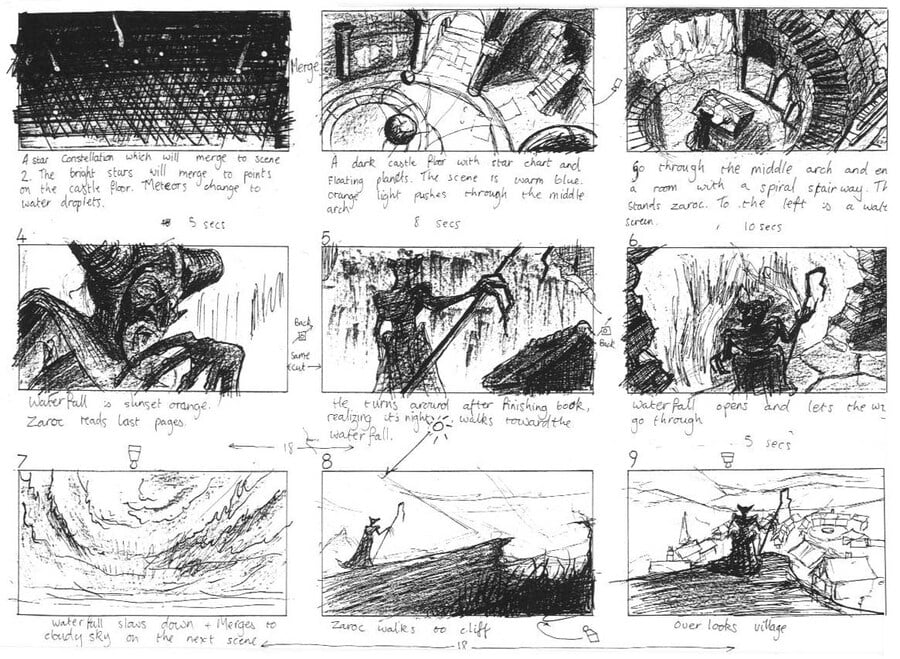

When he was alive, Fortesque was a liar and a charlatan; he attainted a position of power and influence in the Kingdom of Gallowmere thanks to his tall tales and fabricated exploits. However, when the land was faced with genuine peril, Sir Dan found himself pushed to the frontline where he promptly perished in the opening seconds of battle. Gallowmere’s armies nevertheless triumphed over the sinister Sorcerer Zarok, and afraid that he would look a fool for giving such a coward high office the King decided to venerate Fortesque as the saviour of the land. Years later, Zarok returns and unwittingly reanimates Sir Dan’s decomposed corpse – giving the pathetic knight a second chance to redeem himself. Game on.

Chris Sorrell, previously famous for creating the loveable aquatic secret agent James Pond, is the brains behind the MediEvil concept and makes it clear that he wanted his game to possess a unique lead character from the outset. "We worked with a script doctor named Martin Pond, looking for more of a back-story for Dan. Martin made the brilliant leap that Sir Dan could have been a pompous failure in life whose reincarnation was his one shot at redemption." This distinctive plot – twinned with Sir Dan’s unusual appearance – turned out to be quite appealing to some sectors of the gaming community, as Lead Designer Jason Wilson explains: "Oddly enough, we heard after the games release that a lot of women played MediEvil and they found Dan to be very endearing. I guess it was an antidote to all the macho video game characters. Apparently Dan was something of a sex symbol in France!"

But the road to creating a video game sex symbol for our European cousins – not to mention one of the most enjoyable platform romps of the 32-bit PlayStation era – was not an altogether smooth one. Prior to the development of Sir Daniel’s debut adventure Sorrell had endured a rather torrid time on other projects. "I was asked to help out on some new edutainment products that Millennium had just signed up to create, based around Raymond Briggs’ Snowman and Father Christmas books," he recounts. "Once these products were finally complete I think management took pity on me and rewarded me with the chance of making my dream game. There were a few ideas I’d been bouncing around for a while and in particular two sources of inspiration that I felt we could combine in a unique way." And what exactly were those two inspirations, pray tell? "Ghosts ’n’ Goblins was one and the other was a love for Tim Burton’s art style, as typified in The Nightmare Before Christmas. Logically this led to the concept of an undead knight, who was christened ‘Dead Man Dan’ in my first concept proposal."

Sorrell and Wilson’s predilection for all things gothic helped to shape the unique theme of this fledgling project. "I was very lucky that from the earliest stages I was able to work with Jason," explains Sorrell, who has thankfully put his days of wearing black eyeliner behind him. "I guess there’s no denying that we both had ‘goth’ tendencies and we were equally excited to create a game borrowing from such sources."

Considering the humble size of the studio, MediEvil was to be an epic project. “Millennium was a small company with big ambitions; we needed to swiftly gain publisher support in order to finance those ambitions," explains Sorrell. "Consequently the first year of development was as much about creating materials to sell the game as it was building the design. Although we knew we wanted to make a console game, there was no certainty of which platform it would be on. For a while we thought we might be signing up with SEGA – we even started work on the Saturn – but it wasn’t until about ten months into development when we met with Sony. Fate smiled upon us and we had our dream opportunity of building the game, from scratch, as a PlayStation exclusive."

Sony’s support certainly helped ease the financial burden, but making the transition from producing 2D games to 3D ones wasn’t easy. "It was a huge challenge," reveals Sorrell. "None of us had built a full 3D game before. Of course since so much was new, there was a really gratifying sense of achievement as things started to function. I remember the first time we saw the textured 3D world running in-game… it was moments like that which really brought our team together." Wilson concurs. "We were constantly amazed when we got a 3D object on screen or a texture on a cube, it was like we were unravelling DNA or something."

The fact that 3D gaming was really starting to come of age also helped the team. "During development Super Mario 64 arrived," remembers Sorrell. "We played an import copy and were blown away by how well it brought those familiar Mario mechanics into 3D. Tomb Raider was another game that couldn’t help but make an impact, and then there was the first Crash Bandicoot game that set such an amazing visual standard. We were sufficiently under way that none of these games really changed our plan, but they certainly helped us to understand how we might solve some of the challenges we were facing in building a 3D action game for the first time."

An intense development period resulted in some strange additions to the game. "We spent many long nights without sleep trying to finish the game," explains Wilson. "One night we were eating pizza and I was talking about my love of the Alien movies and we then decided to add a bonus level where Dan is shrunk to the size of an ant in order to free cocooned fairies from an ant’s nest, it would play out like a silly version of Aliens. But I didn’t just want normal boring fairies so I decided they looked like mini Bob Hoskins so we made the Fairies sound like gruff bad-tempered cockney gangsters. I think these days the powers that be would just think we had gone mad and ask for it to be taken out." Sorrell also has fond memories of this bizarre stage. "We already had more work on our plate than we knew what to do with, but we were so enamoured with the idea of a tiny Dan running around fighting giant ants that we somehow managed to swap out some other areas to squeeze it in."

Late in development Sony requested that MediEvil should support the (then) new PlayStation analogue controller, which turned out to be a particularly fortuitous event. "I was so glad when we were asked to include support for the new pad," comments Sorrell. "It was quite a way into development and we were certainly struggling to capture even a fraction of the fluidity and intuitiveness that Mario 64 was so effortlessly offering thanks to the N64 controller. Once our new prototype pad arrived, it was actually really simple to hook up a camera-relative control system and after a small amount of debate we decided to make both analogue and digital controls camera-relative, using a weighting system to allow this style of control via the 8 directions of the D-pad."

As production progressed, internal rumblings at Millennium caused Sorrell and his team some sleepless nights. "We were working very closely with Sony at a time when the portion of the Millennium that had developed Cyberlife – an AI technology first used in the PC title Creatures – was rather more concerned with developing that technology than in developing regular games. They were looking to sell the ‘traditional’ games division. We reached a point where it was looking quite possible that we might be sold to a company that many of us thought would be a really bad partner." Sorrell knew that he had to act in order to safeguard his project. "I took a huge personal gamble and arranged a clandestine meeting with our Sony Producer. I told him what was happening, and that I could imagine nothing better than if we could finish development of the game as a first party Sony studio. Fortunately, a few months later we became Sony’s second UK development studio."

The act of promoting video games is never an easy task and the MediEvil team had some interesting encounters during the development of the advertising campaign for the game. "For some reason our marketing folk were always wanting us to visit graveyards for developer photoshoots," explains Sorrell. "We got away with it a few times, and then there was an occasion where having set up all the cameras, a vicar suddenly emerged, pressing us as to why we were filming on church property. Knowing that promoting an ungodly game with a skeletal lead character might not be the most popular angle with the clergy, we made up some baloney about how we were a student group filming a documentary on local churches. Somehow he bought it, and let us continue filming!"

MediEvil repaid Sony’s faith several times over and was a massive success on both sides of the Atlantic when it was released in time for Halloween ‘98. Sorrell is especially pleased with how it performed. "It was the best possible vindication of the enthusiasm and belief we’d long had in the project. It was especially exciting that SCEA were so behind the game, since this was an entirely European project with a very English sense of humour. For me, a real highlight was taking MediEvil to E3 in 1998 and seeing one of the official E3 shuttle buses emblazoned with characters from the game."

A sequel was inevitable, but sadly Sorrell wasn’t as involved as he would liked to have been. "I made a really stupid decision after MediEvil. I was given the opportunity to come up with a brand new game for PS2 – which would become Primal – and I took it. I had a few new MediEvil ideas already scribbled down, but I moved onto creating the concept for this new PS2 project and James Shepherd took the helm on MediEvil 2." Even so, Wilson is full of praise for Sorrell’s influence on the second game. "Chris came up with the marvellous idea of setting the game in the Victorian era with all the characters of Victorian literature," he explains. "But he ended up working on Primal, so I just ran with the idea with a new team which was fun but I took more of a back seat in terms of design." Although he wasn’t as involved as he would have liked to have been Sorrel is nevertheless pleased with that was achieved with MediEvil 2. "All told I think they did a nice job with the sequel and I was certainly pleased to see it meet with further success in the market."

Bizarrely, the franchise bypassed the PlayStation 2 altogether. "Although the second one did well, it didn’t scream ‘must make a sequel’ to the management," recalls Sorrell. "James Shepherd had the opportunity to create his own game and quite understandably took it – this became Ghosthunter. Since we were only a two-project studio, Dan’s main PS2 opportunity had passed. Later in the PS2’s lifetime I actually pitched a MediEvil 3 concept but sadly it wasn’t to be."

The next outing for Sir Daniel would be the PSP remake MediEvil Resurrection, released in time for the portable console’s launch in 2005. "By this time our studio management had changed, and although I stressed how much I would have loved to work on bringing MediEvil up to date, the boss wanted me to work on another project instead," laments Sorrell. "Given my interests and strengths I think that was a really dumb move. Don’t get me wrong, there were some very talented people working on MediEvil PSP and they did an awesome job, especially considering the time constraints they were up against. But I was really sorry to see certain characters needlessly redesigned and frustratingly powerless to stop it." Wilson’s involvement was slightly more significant – he supplied Dan’s voice – but he too was disheartened with having to watch something he dearly loved get needlessly tinkered with. "It was a strange feeling to see something you loved being remade by others. I now know what all those directors feel like when their movies are remade."

Sorrell and Wilson have gone on to enjoy successful careers since MediEvil but both confirm that they harbour a special affection for the exploits of the hapless Sir Dan. "I’ve worked on many games but none of them have a place in my heart like MediEvil… it’s gratifying that it is considered a classic," comments Wilson. Sorrell is in agreement. "Nothing I’ve worked on since has come close to offering the creative freedom and ‘anything goes’ spirit that characterised MediEvil’s development," he says. "We were a young, largely inexperienced team that bonded behind a desire to make the most fun, charismatic game we could. All told, I think the spirit and appeal of MediEvil is a reflection of the crazy experiences and sheer fun we had making it. It’s a sad fact that games just don’t tend to be made like that any more."

This article originally appeared in full in Retro Gamer magazine. It is reproduced here with kind permission.

Comments 14

Absolutely superb article, @Damo! A truly brilliant read.

I never played MediEvil on the PS1 or the PSP. Hmmm. Wonder if it's any good.

Great article! Always interesting to read about how games are made.

@SecondServing one of the best game ever word up son

Really nice article!

I'm happy to own all three games, as well as the other games mentioned from that era.

Game collection is fun, everything comes back.

Great read. I've recently fired up my PS1 and gave this game a quick play after hearing it's getting a remaster.

One thing I hope that's updated are the inverted camera controls. Like many games from the 90's and early 00's they're inverted without the option to 'un-invert' (that I could find). I could just about get used to it on the vertical axis, but not the horizontal one.

It goes to show how controls have evolved. This never used to be an issue for me. In fact I preferred them inverted (certainly on the vertical axis with games like Starfox), but now games border on unplayable when I can't uninvert them. I've got soft in my old age!

Nice read, interesting to see the story behind the game. Great game, can't wait to see the remaster.

Great article indeed, I will finally play this classic now, so glad that they are bringing back Medievil, this game will be day one for me.

Great stuff. I only ever had the demo, so I don't know how I'll fare with the rest of the game, but watch me absolutely sail through level one.

@GravyThief I never understood why games have inverted controls anyway its terrible.

Its nice to read how much he loves the character Sir Dan cant wait to play it.

@Flaming_Kaiser it's because you need to imagine you're controlling a stick at the back of the head of the character. Pushing it up means the head faces downwards, pushing it down means the head faces upwards. Same for left and right. This was fine back in the day when ALL games had controls that were inverted. The problem started when some games had them uninverted without an option to change (well done those people), so you had differences between games. Since then most games have had uninverted controls, which meant that's what I now see as normal. If all games were consistent and followed one standard, or all games had an option for both, this would never be an issue. But of course not all games designers are intelligent, so hence we are where we are.

Really enjoyed reading that. Great article. Looking forward to this release now.

dark souls crossover please happen

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...