Republished on Tuesday, 29th September 2015: We're bringing this article back from the archives to celebrate the PSone's big 20th Anniversary in Europe today. The original text follows.

Originally published on Thursday, 9th August 2012: It's almost impossible to conceive it now but prior to the 32-bit PlayStation's launch in 1994 there were real doubts over its chances in some sectors of the specialist press. Over 100 million hardware sales later, such pessimism seems woefully misplaced, but it's easy to forget just how many hurdles Sony had to overcome to make a success of its first piece of video games hardware – and media scepticism was the least of those problems.

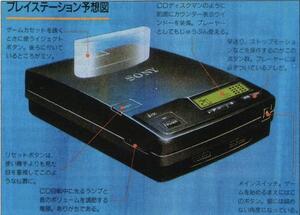

The PlayStation concept actually has its roots way back even before the 16-bit generation had hit the marketplace – 1988, to be precise. Always thinking a few steps ahead of its rivals, Nintendo was actively courting manufacturers to create some kind of expanded storage device for its Super NES console, which was in development and due to hit the market in just over a year. Sony – in conjunction with Dutch electronics giant Philips – was working on a new format called CD-ROM/XA, a new type of compact disc which allowed simultaneous access to audio, visual and computer data, making it thoroughly compatible with the medium of interactive entertainment. Because Sony was already being contracted to produce the SPC-700 sound processor for the SNES, Nintendo decided to enlist the electronics manufacturer's assistance in producing a CD-ROM add-on for its 16-bit console.

For Sony, it was a dream come true. Having been instrumental in the production of the ill-fated MSX computer format, the firm never hid its desire to become a key player in the burgeoning video game business. Therefore, an alliance with what was unquestionably the biggest and most famous name in the industry would not only help elevate Sony's standing, it would also enable the company to set the wheels in motion for its ultimate plan – to put its consumer electronics experience to good use and produce its own video game hardware. The industry was growing at an alarming rate thanks largely to Nintendo's hugely successful NES and Game Boy systems, and Sony was keen to obtain a foothold in this lucrative business.

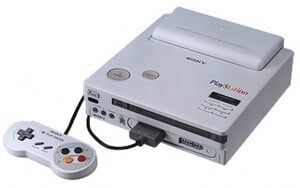

The initial agreement between the two firms was that Sony would produce a CD-ROM expansion for the existing SNES hardware and would have licence to produce games for that system. Later, it was supposed, Sony would be permitted to produce its own all-in-one machine – dubbed PlayStation – which would play both SNES carts and CD-ROM games. The format used by the SNES-based version of the PlayStation was called “Super Disc" and Sony made sure that it held the sole international licensing rights – in other words, it would profit handsomely from every single SNES CD-ROM title that was sold. It was a match made in heaven; Sony would instantly gain a potentially massive installed base of users overnight as the SNES was a dead cert to sell millions of units. SNES users would upgrade to the new CD-ROM add-on when they knew that Nintendo's cutting-edge games would be coming to it, and Sony would make money on each software sale. What's more, once the all-in-one PlayStation was launched, Sony would gain even more in the way of profits and become a key player in the video game industry. The man behind this audacious scheme was Ken Kutaragi, the engineer also responsible for producing the aforementioned SNES sound chip.

However, behind the scenes Nintendo was predictably far from happy with the proposed arrangement. It was very protective of its licensing structure, which allowed it to extract massive royalties from third-party publishers. Allowing Sony leverage in this sector would only damage Nintendo's profitability; the Kyoto-based veteran reasoned that it should be making the majority of the profit on SNES CD sales, not Sony. The plan – if it came to fruition – would ultimately benefit Sony far more than Nintendo; the former would merely be using the latter as a way of getting a ready-made market share and would eventually become a determined rival as a result. Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi was famous for being particularly ruthless in his business practices, but what happened next is one of the most infamous double-crosses in the history of the video game industry.

It was at the 1991 Consumer Electronics Show – or CES as it was otherwise known – that Nintendo dropped the bombshell. Sony went to the event full of enthusiasm and on the first day proudly announced the details of its new alliance with Nintendo, as well as news of the “Super Disc" format and the impending development of the SNES-compatible PlayStation. Sony had less than 24 hours to soak up the palpable level of excitement generated by this press conference before Nintendo confirmed that it was in fact working with Philips on the SNES CD-ROM drive. Yamauchi had gone behind Sony's back at the last minute to broker a deal with the Dutch company – a deal which was predictably skewed in Nintendo's favour - leaving Sony publicly humiliated at the very moment it had expected to usher in a new era as a serious contender in the video gaming arena. At the time, Yamauchi and the rest of Nintendo's top brass were suitably pleased with their skulduggery; such swift action had prevented Sony from taking a sizable bite out of their profits. As it happened, the planned Nintendo-Philips alliance resulted in little more than a handful of risible CDi-based Nintendo licences, and the abject failure of Sega's Mega CD seemed to lend credence to the viewpoint that expanding existing consoles was mistake, so while Nintendo had protected its best interests by leaving Sony at the alter in such degrading fashion, it actually gained little else of note – aside from a dogged rival.

Yamauchi was famous for being particularly ruthless in his business practices, but what happened next is one of the most infamous double-crosses in the history of the video game industry

Sony had, by this point, poured a significant amount of cash into the proposed PlayStation concept. It had even moved as far as the prototype phase, with PC CD-ROM titles such as Trilobyte's 7th Guest being mooted as possible launch games. Despite the tumultuous events of the 1991 CES, a deal was signed between Nintendo and Sony that would allow the latter to make its machine compatible with SNES CD-ROM titles – with the proviso that Nintendo would retain all software royalties. Although it was nothing more than a clever stalling tactic by Nintendo to keep Sony from entering the market on its own, this proposed alliance nevertheless kept the increasingly frustrated Kutaragi and his team busy. However, by 1992 it had become clear that such a union was going nowhere; Sony cut off communication with Nintendo and the company was painfully close to withdrawing from the video games arena for good.

Only Kutaragi's intense resolve and determination prevented the PlayStation dream from ending in '92. During a meeting with Sony president Norio Ohga in order to decide the future of the project, Kutaragi made bold claims about the kind of machine he had been developing. He argued that the 16-bit PlayStation – with its reliance on a union with the incumbent (not to mention untrustworthy) Nintendo – was a dead-end; the only option was to go it alone and create a brand new piece of hardware capable of shifting 3D graphics at a hitherto unprecedented rate. When Kutaragi's ambitious proposal was greeted with derision from the Sony president, he presented another side to his argument – could Sony's pride allow it to simply walk away when Nintendo had so blatantly abused its trust? By making the PlayStation project a success, the company would experience the sweet taste of revenge at the expense of its one-time ally.

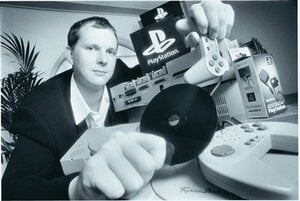

Kutaragi's speech hit a nerve and early in 1994 Sony confirmed that it was entering the video game arena with its own console, and even formed subsidiary Sony Computer Entertainment in order to oversee the new venture. Keen to differentiate this new project from its previous namesake, Sony branded it the “PlayStation-X" – which gave rise to the abbreviation PSX, which is still used even today — even though the X was later dropped when the console was officially launched. Early reports were impressive, with some developers confidently proclaiming that Sony's console would blow away the competition. Despite the company's wide entertainment portfolio – which included music label CBS Records and Hollywood studio Colombia Tri-Star – Sony boldly decided not to focus on the multimedia market, as its rivals Philips (with its CDi) and 3DO had done, to their great cost. Instead, the PlayStation was unashamedly proclaimed as a dedicated gaming machine, with SCE's Director Akira Sato confidently stating that “If it's not real-time, it's not a game" – a thinly-veiled criticism of other CD-based consoles and their reliance on FMV titles that featured live actors but little interaction. The sheer power of the new system shocked other players in the industry; Sega of Japan president Hayao Nakayama was reportedly so furious when he read the almighty specs for the PlayStation that he personally visited Sega's hardware division and gave them a stern talking to. His tirade would result in the Saturn – Sega's entrant in the 32-bit console war — getting an additional video processor to boost its graphical muscle but this ironically would make the system harder to program for – an issue which had severe ramifications in the future.

When you take into account Sony's position as one of the world's foremost electronics manufacturers, it's hardly surprising that the original PlayStation was a highly desirable piece of kit. Unmistakably a games console but showcasing a hint of mature design, the machine seemed to speak to those gamers who had cut their teeth on the likes of the NES, Mega Drive and SNES and were now ready to progress to an entirely different level of challenge. Everything from the two-pronged joypads to the removable memory card storage system seemed to drip sophistication. Sony later revealed the numerous hardware designs that had been considered before the final version was decided upon; this was the work of a company that was taking its entry into the video games market very seriously indeed. Kutaragi – and the entire project in general – had come under fire from high-level Sony executives who argued that video games were toys for children; therefore, one of PlayStation's key aims was to challenge that view. As a result, the final design for the machine was sleek and serious, mimicking the appearance of a top-end piece of audio-visual equipment rather than a games-playing device.

However, while this posturing caught the attention of gamers the world over, some industry experts were less enthused, citing Sony's poor track record in the industry up to that point. The company's software publishing arm — Sony ImageSoft — had so far failed to generate any titles of note, pushing half-baked movie licences such as Cliffhanger and Last Action Hero onto store shelves to the complete indifference of the games-buying public. Indeed, software was one area in which Sony was at a distinct disadvantage. Sega and Nintendo had highly-talented internal development teams that traditionally produced the best software for their respective consoles, but Sony lacked this key feature — although it was at least attempting to rectify the issue by purchasing highly-rated UK code shop Psygnosis, which would go on to publish vital launch titles such as WipEout and Destruction Derby. Still, there was an overwhelming feeling that although Sony was perceived to be doing everything right, it would ultimately fall at the final hurdle; Sega and Nintendo would continue to fight it out, just as they had done during the previous format war. Sony didn't know videogames, the critics cried. Thankfully, the firm managed to secure the assistance of a company that certainly did know something about the industry: Japanese arcade veteran Namco.

Pac-Man creator Namco was undergoing something of a resurgence thanks to the incredible impact made by its 3D coin-op Ridge Racer. A texture-mapped tour de force, the game was unquestionably a cutting edge piece of programming and had given its parent company the ability to leapfrog persistent rival Sega in arcades. When Namco revealed that it was porting its hugely successful racer to the PlayStation, it caused quite a stir. The notion that Sony's new console could replicate an arcade title that cost thousands of dollars created astonishing levels of expectation, and this only increased when the first shots of PSX-based Ridge Racer were released to the public. Coded in an incredible six months, the game might not have been arcade-perfect but it did enough to cement Sony's position as a key player, purely because it made Sega's heavily-delayed in-house conversion of its Daytona USA coin-op look decidedly second-rate by comparison. Elsewhere, the PlayStation's visual prowess was demonstrated by exquisite third-party titles such as Jumping Flash and Battle Arena Toshinden, the former being a ground-breaking (if shallow) 3D platformer and the latter a likeable (if uninspired) one-on-one brawler. Toshinden couldn't hold a candle to Sega's Virtua Fighter port when it came to gameplay, but it was nevertheless a fundamental game in Sony's arsenal because it looked far, far better. From screenshots alone, it was clear that the PlayStation had the edge in terms of raw power.

The Japanese launch took place on December 3rd, 1994 – a handful of days after Sega had shifted a stunning 200,000 Saturn consoles on its first day of sale. Priced at ¥39,800 (around £250/$400) in today's money) the PlayStation sold strongly, although the Japanese public seemed to gravitate towards Sega's console more, possibly because Virtua Fighter — despite the slightly unimpressive Saturn conversion — was the country's number one arcade title at the time. Both formats started out fairly evenly, but as the months rolled by Sony was able to deliver on its promises thanks to sterling releases from Namco, Konami and Capcom, while Sega's in-house projects stalled. Ironically, Sony's reliance on third party developers proved to be in its favour; because it needed outside assistance the company had made great efforts to get software support, while it could be argued that Sega – brimming with confidence over its own internal development talent – was less active in courting developers. Sony had made the PlayStation as accessible as possible for third parties, and it was reaping the benefits.

The technological gulf didn't do the PlayStation any harm, either; titles such as WipEout looked gorgeous, with transparent textures and eye-popping lighting effects. Sega's machine lacked both of these embellishments, and thanks to its complex dual-CPU setup, required the best coders to really get the most out of it. Many didn't bother to make the effort, and instead flocked to Sega's rival. Numerous third party studios were getting stuck into PlayStation game production, and a string of classic titles began to emerge. Tomb Raider (ironically a Saturn title before it was released on Sony's platform), Tekken 2, Soul Blade, Ridge Racer Revolution and Resident Evil all contributed to the PlayStation's wide and varied catalogue of titles.

Sony had made the PlayStation as accessible as possible for third parties, and it was reaping the benefits

The Western launches were equally successful, with Sony managing to undercut the retail price of Sega's Saturn in both North America and Europe. In Europe especially Sony displayed a masterly grasp of how to market a games machine to a more mature audience; the company knew that those gamers which had grown up with the 8-bit and 16-bit consoles were gradually reaching adulthood and would therefore require more “grown-up" gaming experiences. While Sega and Nintendo focused on building recognisable mascots to appeal to youngsters, Sony released the PlayStation with a range of software that was unashamedly adult in tone. The aforementioned WipEout featured a soundtrack that showcased the talents of real recording artists, such as The Chemical Brothers and Leftfield, while visceral top-down shooter Loaded not only featured excessive gore and allusions to transvestism, but also enrolled the assistance of grebo-rock outfit Pop Will Eat Itself. One thing was clear – Sony wasn't aiming for the Mario and Sonic audience with the PlayStation.

Sega's challenge soon began to falter, and so Nintendo — the company that had double-crossed Sony a few years previously — became the next opponent. The firm responsible for such classics as Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda had been making confident noises about its cartridge-based Ultra 64 (AKA: N64) console for some time, and although it wouldn't be ready until 1996, Nintendo went to great lengths to encourage gamers to hold off on buying a 32-bit machine. Sadly, the decision to stick with the expensive cartridge format would cost the firm the support of one of its most prized third party publishers: Square Soft. Although the highly anticipated Final Fantasy VII had been confirmed as an N64 release, Square eventually switched development over to Sony's machine, citing the limited storage and high unit cost of cartridges. Final Fantasy VII was going to be the most epic game yet conceived, and it needed as much storage space as possible. Only CD-ROM could offer this, Square argued. Nintendo's loss was of course Sony's massive gain; published in 1997, Final Fantasy VII was a worldwide smash-hit, selling 10 million copies in the process. This success established the console as the leading platform of its generation and subsequent system exclusives such as Konami's Metal Gear Solid and Polyphony Digital's seminal Gran Turismo cemented this lofty status even further.

With both Sega and Nintendo subdued, Sony's dominance was assured. So tight was the company's grip on the marketplace that even the launch of Sega's technically superior 128-bit Dreamcast in 1999 was unable to upset the status quo. With millions of units sold and a more powerful successor – the PlayStation 2 – waiting in the wings, 2000 saw Sony release a new iteration of its 32-bit console in the form of the PlayStation One, or PSOne for short. Smaller, sleeker and sexier, it boasted enhanced functionally which allowed it to link to mobile phones and even supported a fold-down LCD display, giving it a small degree of portability. The revision was a triumph and enabled the aging machine to remain relevant in a marketplace that was gradually leaving it behind in technological terms.

Sony ceased manufacturing the PlayStation in 2006, giving the console an impressive production lifespan of 11 years. During that time it redefined the world of video games, granting gamers their first legitimate taste of 3D visuals and making the oft-derided hobby a cool and relevant pastime. Of course, such activity earned Sony – and by association, its console – a fair degree of scorn also, but few would have the temerity to debate the PlayStation's incredible influence on modern interactive entertainment. Without it, the gaming landscape today would be near-unrecognisable — and this very site wouldn't even exist.

The feature was originally printed in its entirety in Retro Gamer magazine, and is reproduced here with kind permission.

Comments 38

Absolutely brilliant report Damien — I thoroughly enjoyed reading this.

Great article!

A few bits in there I'd never read before too.

I think The PlayStation was the last time I was truly excited (nothing beats the Christmas my brother and I opened our MegaDrive!) to get a new console.

Aaaaaaand we thought it was broken!!

Turned out my uncle (who had taken charge of setting it up) hadn't pushed the quite horrible original AV connector all the way in to the back of the console.

Then Ridge Racer Revolution, Warhawk and battle Arena Toshinden were mine!

Incidently, while boxing up my 60GB PS3 to trade I found my old PS1 GTA2 branded memory card. Still has all of the saves, even Crazy Ivan!! ;-P

That SNES/PS1 hybrid is crazy!

Very interesting article though. Such a shame seeing Sony in the state they are in now, considering how they completely changed the market with PS1 and 2. Still, bad decisions and poor launches aside, the PS3 is still the best piece of tech in my house. I challenged a whole bunch of my 360 playing friends to give me ONE reason to own an Xbox over the PS3 (completely unbiased, I promise. Put my money where my mouth is and said I'd get on if they could come up with a reason). Needless to say I still only own a PS3.

I had such a great time reading this! Really well-written and I'm so looking forward to reading more articles from you

Excellent enlightening article. I commiserate about your PSP's; I am on my third set of right hand buttons for my PSP.

Fantastic read man, always felt like that point was like the event horizon in gaming.. very cool stuff. Thanks

@ the words "risible", "abject" and "credence"Aaaaand I'm off to the dictionary.

On a more related topic... I'M NEVER BUYING ANOTHER NINTENDO CONSOLE AGAIN O.O

its sad now how things have changed...ps3,psp and vita... getting from bad to worse...

@Damo Fantastic work man! Such a brilliant read, and there's a few bits in there that I actually didn't know.

Thanks for the kind comments, guys. Glad you like!

Nice article. Personally I never liked the PSOne or PS2, preferring my N64 (nothing has come close to Mario 64 in over 16 years), Dreamcast and GameCube but was always impressed by how it helped make video games the huge success they are nowadays. When I was at school I was laughed at for bringing my Gameboy out at breaks to play Metroid or Pokémon, but these days I'd be considered 'cool'. Video games are now - as we all know - the biggest form of entertainment on the planet and that's been helped a lot by Sony.

One sided contracts/deals, and double-crosses aside, I'm glad Nintendo and Sony stayed seperate.

I like that white Playstation/SFC prototype.

A good read. Includes some details I hadn't read about before.

@rastamadeus

I'd still laugh at you for playing Pokemon

@KALofKRYPTON Hey now! Don't hate on Pokemon. Even as a 30yr old hardcore gamer, Pokemon is a much beloved and respected franchise in my eyes. I don't play every release, but every few years, there's always room for a good Pokemon quest. It's a series that sucessfully transitions young gamers into a deeper gaming experience, and that in itself gets the utmost respect from me.

I was a big time ps1 supporter.Still have mine and still gets played from time to time

@Slapshot

Hahahaha, they've just never appealed to me- that- and the fact that I ended up living with a bloke at Uni who was fanatical about all things Pokemon, scarily so!

He paid for all of us he lived with (7 all in) to go and watch the movie, time I'll never get back hahahaha

They're like Warcraft to me really- pretty spreadsheets.

I like plenty of dross, not really having a go- each to his own. I just received via the work post the PS2 Star Trek Encounters- widely terrible reviews, but I think I'm going to really enjoy it!

@Savino They weren't but Hiroshi Yamauchi was. A truly terrifying man.

@KALofKRYPTON Each to their own but the main Pokémon games are nearly always deep, engrossing games which are fun to play. Black/White 2 are easily in the top ten games of the year too.

@JavierYHL

Well, there's no accounting for taste, particularly here in North America where you have the most clueless consumers in the world (I'm from the U.S. so I hate admitting it, but the truth is the truth). The PS3 is by far the best bang for you buck on the market but Xbox is what gets shoved in everybody's face and it's very easy to manipulate people in NA. Gotta give MS credit for being good at advertising, sadly they suck at everything else. Hopefully Sony can turn things around soon and climb back to the top because if the game industry keeps going in the direction it has been the last few years it will soon be dominated by Xbox and that's the absolute last thing we need.

great read! Yup, PlayStation (since PSOne) has been my favourite consoles since, just because they let the third party have a chance on there systems, unlike Nintendo that takes all the glory or itself.

Also I have to say, I love how Sony came into the market to basicly gave Nintendo a well deserved finger for screwing them over

It's funny how one decision can change the course of the industry for the next one or two gens. Had Nintendo gone with CD over cartridge, FF VII likely comes out for N64 and you probably don't see the Playstation brand reach the heights it did. Then in 2006, after at least 9 or 10 years of dominance the likes of which the game industry had never seen, Sony hands it all back with the decision to charge $600 for the PS3. I actually don't think that was an unfair price but it was out of the mass market range and Sony is still yet to fully recover from that.

I found the article very informative. Some parts could have been structured differently to avoid using the word "however" at the beginning of a sentence. Whenever I see that word, I am reminded that many folks constantly use that word with great force before making a statement in contrast to a previous statement. Even though some folks use that word with less force than others while beginning a sentence or contrasting parts of a sentence, I would use that only when telling someone they may do some activity in any manner they want.

@hydeks

I don't take pleasure in how Sony entered the video game market without the help of Nintendo. Also I would not use references to rude gestures (such as pointing with the middle digit of a human hand) either.

The original playstation did have a few good platforming games

such as Crash Bandicoot.

I loved the original PS because of all of the variety on it. Sadly anything since then didn't end up good.

...

@Savino Well it was the more sensible for them, Nintendo nor Sony would exist now.

just imagine if Sony and Nintendo had stayed partners would we now be playing Uncharted on the Wii U?

I'm glad things turned out the way they did. I've nothing against Nintendo, but having never been a fan of their games, I feel Sony's hardware would be wasted on them. Better for them to have pushed ahead on their own and redefine gaming as they did.

I'm glad things turned out the way they did. I've nothing against Nintendo, but having never been a fan of their games, I feel Sony's hardware would be wasted on them. Better for them to have pushed ahead on their own and redefine gaming as they did.

Playstation/hardware has come a long way. Check out the PSone specs compared to PS4:

http://www.engadget.com/products/sony/playstation/1st-gen/specs/

@Bad-MuthaAdebisi

If anybody running Sega had half a functioning braincell, the Genesis could've done more than just given SNES a run for its money.

@Gamer83

Coming from a family that made its fortune out of importing Sega hardware and software I couldn't agree more. Sega of America and Europe to a lesser extent had some wonderful ideas, but Japan just wouldn't listen to them. Sega was "cool" way before PlayStation was and they could've banked on it, instead they managed to confuse the consumers with countless add- ons and hardware that was impossible to work with. The DreamCast deserved a better faith, but by that time they had already lost the war, although we went on to sell more of them than the PS1 ever did in our region (I wanted to say PS2 as well, but I think PS2 eventually overtook DC sales).

When I think of how everything went down back then, with Sega coming strong out of the 16- bit era, screwing up the 32- bit and bringing out their next console really early, I can't help but think about Nintendo. Sure, their "Genesis" in this timeline, the Wii, did a lot better than the Genensis ever did and Nintendo is therefore sitting on a tremendous amount of cash, but bringing a new console when the others are just gaining momentum because the other one just didn't sell after a reasonable start...sounds quite Sega to me!

@Boerewors

NES was the system that introduced me to games, but I'd say it was the Genesis that made me a 'gamer.' I couldn't get enough of that console and the games on it. There's no question, Sega had the cool factor, especially here in the States where we love the NFL and the Genesis had the edge with those games. But what happened in the latter stages of that gen was shocking. However, what was especially stupid and what I will never understand is why in the hell a company run by supposedly smart businessmen would think it was a good idea to send a system to retail without telling a single person about it. Unbelievable. I still stuck by Sega. And I was there early on for the Dreamcast, which had a tremendous library and it one of the most forward-thinking consoles ever. I'd still probably be a Sega guy today if it were making home consoles. More than maybe even Nintendo, Sega's games were tailored to its hardware and I miss what the Sega I grew up with brought to gaming.

Seaman for the win!

It would be nice if the PS4 gets PSOne classics with transfer from PS3 and cross buy with the PS Vita.And crash and Spyro on the PS vita.

@Damo Pure gold! thank you Damien. I shall read it by midnight.

Playing Ridge Racer, Tekken and Rayman almost brought a tear to my eye.

HAPPY 20TH ANNIVERSARY SONY PLAYSTATION!

Happy 20th birthday to PlayStation 🎂

I came to the Sony party a little later. My first console was the PS One, with a copy of Final Fantasy IX, and to this day it remains my favourite instalment. Of course, I then delved deep into the huge library of PS games, including FF VII & VIII, MGS, Tomba, Legend of Dragoon, Crash Bandicoot, Spyro, Croc, Resident Evil and WWF Smackdown. I even still remember being wowed by the FMV, which was pretty foreign to me as an N64 fan, as well as the notion of multiple discs for bigger games. As far as I was concerned, it was sorcery!

@Damo: PS1 was the very first gaming console I ever owned, my mom bought it for me as a Christmas 1999 present (I was almost 11).

I think the first 3 games I ever owned/played for it were Animorphs: Shattered Reality, Blaster Master: Blasting Again, and Spyro the Dragon.

I miss demo discs on PS1. Put so many hours into the first featuring Wipeout, Battle Area Toshinden and Jumping Flash!! Sat on my carpet in awe - probably eating too much Monster Munch

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...