In the 1980s, the hobbyist game development scene was absolutely thriving in the UK. Home computers like the ZX Spectrum, BBC Micro, and Commodore 64 all allowed their users to write custom code from scratch, in what was known as the Basic programming language.

As a result, each system had an incredibly dedicated audience of bedroom developers who were keen to hone their programming skills by creating computer games, copying them to cassette, and flogging their wares any which way they could.

It was a golden era of creativity and grassroots development that saw the rise of legendary software houses like Psygnosis and Ocean. Series like WipEout, Lemmings, and Colony Wars genuinely might never have seen the light of day were it not for this pioneering period.

Fast forward four decades to today, and independently-created video games are everywhere. With development tools like Unity being so easily accessible, and an almost limitless number of online storefronts, it’s never been easier to create and distribute vidja.

Games like Stray and Tunic have even featured in Sony’s State of Play presentations. It’s clear that indies are a hugely important part of the industry these days — but there was a time when that simply wasn’t the case.

The Rise of the Home Console

In the late ‘80s, home computers like the ZX Spectrum began to fall out of favour with gamers, and were slowly being replaced by the smaller, more intuitive, dedicated video game consoles. Systems like the NES brought many benefits for players, but the closed-off nature of the platform meant that bedroom developers were largely locked out.

Development kits for these newfangled home consoles were prohibitively expensive for the average Joe, and publishing restrictions were often strict. If you wanted to launch a game, you needed to convince a company with the necessary publishing and distribution grunt that it was good enough to market.

The era of the bedroom developer, it seemed, was over.

Enter Net Yaroze

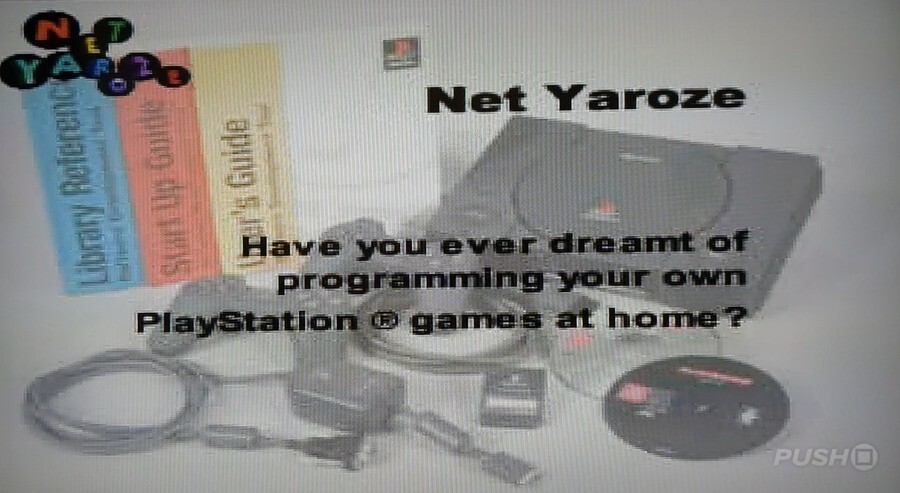

In 1997, long before initiatives like XNA on rival platforms, Sony launched the Net Yaroze – a home development kit for the wildly popular PlayStation, for just £550/$750.

Net Yaroze – literally ‘let’s do it together’ – was conceived by Ken Kutaragi, the godfather of the PlayStation itself. The UK division, however, was headed up by Paul Holman, a man who cut his coding teeth on BBC and Atari computers, and his goal was simple: bring back the bedroom coding scene for the 32-bit era.

The sort of money Sony was asking for in ’97 was by no means a small outlay, but crucially, it was thousands of pounds less than a ‘proper’ PS1 dev kit, and it provided would-be developers everything they’d need to code PlayStation games on their home computers.

Adopters were given access to an online community of hobbyist developers who would share builds of their projects for other members to playtest and provide feedback on. Some Sony devs were even on hand to offer tips and tricks to fledgling creators.

Games like Gravitation saw players racing and battling cursor-like ‘ships’ around 2D arenas by feathering the throttle in zero gravity and pew-pewing lasers at one another. It was a simple, but incredibly fun little game. You can even play it in your browser by clicking here!

Puzzle games were popular, too – Super Bub Contest was a competent and charming Bust-A-Move clone with a cast of oddly lovable characters, and a somewhat unnecessarily bangin’ electronic soundtrack. Seriously, they didn’t need to go this hard.

Stuck on You-roze

So, developers were doing what developers do best – develop! – but it quickly became apparent that the Net Yaroze had some pretty severe limitations.

Certain features like multi-tap support were inaccessible, meaning that 3 or 4-player games were out the window, but perhaps the biggest restriction of all was related to file sizes: as the system didn’t support burning to CD-ROM, the entirety of any Net Yaroze project – sound and all – had to fit within the PlayStation’s paltry 3.5MB RAM.

When you consider that titles like Final Fantasy VIII were filling multiple 700MB-capacity CDs at the time, it’s no surprise that most Yaroze games were incredibly simplistic by comparison. But there was another, more pressing problem for these games: there was no way for anybody outside of the Yaroze community to play them.

The home computers of the 1980s allowed developers to copy their games to cassette and share them freely. Creators could sell their finished games in mail-order magazines, at computer fairs, or even to independent computer stores.

But the Yaroze’s lack of a disc-burning facility meant that none of this was possible. In fact, in order to play a Net Yaroze project, you needed access to the entire development environment – PC and all.

These games, then, were trapped within a community of a few thousand enthusiasts, with no way for the public to go hands-on. That is, until Sony started including select Net Yaroze games on demo discs that came with the Official UK PlayStation Magazine.

A Lasting Legacy

The move raised awareness of Yaroze amongst the public (it’s certainly where this writer first heard of it), and no doubt helped a number of developers get their starts in the industry.

An amateur Japanese developer by the name of Mitsuru Kamiyama crafted an impressive RPG tech demo called Terra Incognita. He’d later go on to become the series director of the Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles series at Square Enix.

The code that Chris Chapman wrote for Total Soccer would eventually form the backbone of the FIFA series on Game Boy Advance and Nintendo DS, while Ed Federmeyer — creator of Haunted Maze — would go on to become lead programmer on The Conduit.

The online community ran for 12 years before finally being pulled in June 2009. There’s no way to know for sure just how many games were created using Net Yaroze, but Sony claimed to have sold several thousand systems worldwide, so it’s only logical to assume a similar amount of projects were at least started, even if they didn’t all see the light of day.

Net Yaroze never did receive a direct successor, but with Sony's strong desire to champion indie games on its platforms self-evident in recent years, its DNA has undoubtedly intertwined with the fabric of PlayStation. Long may that continue.

Do you remember Net Yaroze? Do you remember those iconic demo discs that came with the Official PlayStation Magazine? Feel free to develop yourself in the comments section below.

Comments 19

I'd love to play a Net Yaroze compilation, if only for the nostalgia value. The Haunted Maze (3D Pac-Man-esque shenanigans with zombies) and Time Slip (the mind-bending adventures of a time-travelling snail) were two personal favourites of mine.

Interesting read, thankyou, there's an unboxing video on YouTube

https://youtu.be/zDCIc5rw6XY

I used to love some of these games on the OPM disc back in the day. Some excellent names of games in the article and comments so far but may I also add;

Rocks and Gems

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SfN_K20j4og

Psychon

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4TU2yNbT0k8

Blitter Boy

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=diF0qOWxQ0A

@Thrillho Great games! Blitter Boy was my favourite back then!

I remember the Blitter Boy demo, and one other game called Down. They were probably on the same PSM UK demo disc. I don't have much experience with Yaroze other than that. Very cool idea for it's time though.

Issue 42 of official ps mag in uk had a bunch of great ones as well as first taste of mgs1. I bought every issue after that.

@Bentleyma I played that! It came on a demo disk.

Still have them all somewhere including my favourite, super bub challenge

@Bentleyma I sure do! Loved that game.

Also played Psychon alot that @Thrillho mentioned, totally forgot about that one. Honestly i forgot about all of these games.

But I probably played Gravitation the most, I really miss demos from magazines. Good times.

That's really cool. I wish they did something similar for PS5, but perhaps as a pluggable device instead of a full dev set. AFAIK Unity can only be used for dedicated consoles if you pay for it, so perhaps a Sony device that allowed any custom code access to their APIs could recreate that sense of community again.

A cool time for sure. I remember one of the games had the iconic saxophone death sound in the Pacman like one. Otherwise some really cool tech demos and games came out of this. Not all great but still impressive for the time.

Alien Hominid in 2003 a Newground team game (Castle Crashers, BattleBlock Theater and others later) for sixth gen consoles (one of the few 2D games that looks fun and that I can think of on those consoles too that wasn't on handhelds that weren't just Tetris or something. Like I can think of the puzzle game with the fruit shifting called Super Fruit Fall on PS2/PSP/Wii).

Cave Story also on PC before consoles and it also having it's impact.

Net Yaroze games happening before Indies on Xbox Live, WiiWare or PlayStation Minis (PSP/PS3 mobile or Indies that I find people forget or Nintendo/Xbox gamers don't understand) was something interesting to see then, and it was a good time it seems looking back at what was offered and looking at the good, middle of the road and bad and we have what we have today of Indies of better quality sure but making their own impact.

The Ouya being a Dev Kit and a android console in one making it a good entry to android studio I guess if people cared then complaining about it and it dying. Besides it's issues it was a fair move of a dev kit and console even if it didn't offer the best games on it. Some parts of it were right in what they offered besides a cheap emulator android device too of course for many people later on or homebrew.

@Bentleyma I can't be the only one but I still love it and I'm glad you can still "live" those moments with current technology 😄😁

LOL my OG post was deleted idk why, never had any outside intentions 🤷♀️ I guess my experience in this subject should be left at this, but I do remember these games and their prescence are still available to play, not COPYRIGHTED and are free open source homebrew, I've done nothing wrong here, these games are still available for people new and old to enjoy the retro scene to freely play and enjoy them, idk why I cannot say something like that 🤷♀️ but I'm out if that is the case

@Moonmonkey same I still have the original discs for all net games...this my last post tho, the hypocrisy of this article which is trespassing over this spectrum is still warrant for me to not be able to speak my mind about my experience with these games, a part of history beyond the times of internet, I can't say anything else, my lips are sealed regarding this even tho I've even witnessed a net Yaroze PS1 it seems my presence is not warranted here, why post if you don't want this subject openly discussed? I don't get it at all 🤷♀️ but yeah I'm done here for now....

Very fascinating. I don't think I ever had the luck to try out any Net Yaroze games back then sadly but I have heard about them. Thanks for the read!

Blitter boy is the one that stuck in my mind all those years ago.

That fuzzy lion's head in the picture for the article brings me back lol. SUPER BUB and what a kickass tune it had too.

Another game I remember was "Adventure Game" which surprisingly had 3d graphics and a meta sense of humour. I remember an NPC even made a reference to South Park citing "Hey, at least we have a 3rd dimension unlike those South Park kids" or something like that.

Wow, brings back memories. I had one for about a year with the intention of getting into game programming. Was a bit hard-core for me at the time, though, and sold it after about 12 months.

Wish I'd kept it, quite rare to find nowadays for under £1000.

Edit: Wow, just found the receipt for it, cost me £652 in Feb 1997!

I really wanted one. Not because I wanted to develop games. I just wanted a black PS1 😁

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...